No matter how many legs you have, the basics of animal behaviour apply to us all. Animal training is based upon these principles, and it’s important to have an understanding of what drives your dog so you can set them up for success!

DEFINITIONS

behaviour: anything your dog does!

stimulus: something that is sensed by an organism. Sounds, smells, objects, and other animals’ behaviour in a dog’s environment are all stimuli (plural of stimulus) that are perceived by your dog.

cue: the thing you say or do that ‘tells‘ your dog to do a behaviour (ex. “leave it”, a hand gesture, blowing a dog whistle). Also known as a “command”.

conditioning: learning! An association your dog makes between a thing and another thing. Conditioning can happen intentionally (ex. conditioning your dog to sit when you say “sit”) or unintentionally (ex. your dog learning that you picking up their bowl means food is coming).

reinforcement: any consequence that makes a behaviour more likely to occur. These can be pleasant, like a treat, or relief from something unpleasant, like a choke chain.

punishment: any consequence that makes a behaviour less likely to occur. These can be actively unpleasant, like being hit or scolded, or passively unpleasant, like playtime ending.

marking: calling your dog’s attention to their behaviour (and how you feel about it). “Markers” like clickers, words, or hand gestures, are immediately followed by a consequence. Marking is more often used in reward-based training.

CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

Classical conditioning occurs when a stimulus is paired with another, otherwise unrelated stimulus. You may have heard of Ivan Pavlov’s dogs; Pavlov discovered in 1929 that when dogs were presented with cues like bells at the same time as their food, they began to salivate at the sound of the bell. The dogs learned that bell = food, and the bell sound leads them to expect their dinner.

Classical conditioning happens all the time! Language only exists because of classical conditioning; the word “ball” has nothing to do with the actual object “ball”, we have just learned that that’s what it’s called. For example, many dogs learn that when you put on their harness or reach for their leash, you are about to take them for a walk. Classical conditioning can work in your favour or against you, so it’s important to know what it is and how it works.

Marking a behaviour during training uses classical conditioning to teach your dog that the marker is immediately followed by a consequence. Over time the marker will represent or even replace the consequence if you forget your treat bag, so your dog knows that whatever they just did was good or bad. Clickers, “yes”, or “good dog” followed by a reward are great ways to mark good behaviour! Marking bad behaviour requires the use of aversive tools, which have been proven to do more harm than good (more on that later).

Under the direction of a qualified trainer or behaviourist, classical conditioning can also be used to desensitize dogs to stressful events like heavy traffic or other dogs barking. By presenting a pleasant stimulus (ex. food or attention/comfort) at the same time as an unpleasant stimulus (ex. loud noise), your dog begins to associate the scary thing with something positive. With enough repetition, the unpleasant stimulus stops being so scary.

Classical conditioning does not work on behaviours (that’s operant conditioning – see below). Desensitization works because stress and fear are not behaviours, they are emotions. Desensitization does not condition your dog to seek comfort from you every time they hear a loud noise; it makes sure that they can hear a loud noise without needing comfort.

OPERANT CONDITIONING

Operant conditioning, sometimes known as instrumental or behavioural conditioning, occurs when a behaviour is tied to a direct consequence. It was discovered as an extension of classical conditioning, but is specific to your dog’s behaviour rather than just stimuli in their surroundings. This also happens naturally (ex. sticking your hand in a wasp’s nest leads to wasps stinging you) or intentionally (ex. your dog gets praise from you for chewing on a toy instead of the furniture).

While classical and operant conditioning are defined separately, they both occur simultaneously! For example, even with familiar or basic cues like “sit”, your dog may have difficulty in new environments. This is because the classically conditioned cues that go along with the sound of “sit” are different in new places (ex. in your house vs. at the park). They have to ‘re-learn’ the “sit” cue in a new environment with new stimuli, like people/dogs nearby, outdoor smells, their collar/harness/leash on, and standing on grass. This is why it is so important to practice cues in different environments, building up to more distractions and new information! Your dog may have great recall across your backyard, but the contextual cues are very different when you actually need to use it.

Operant conditioning is based on the observation that the consequences of a behaviour make it more or less frequent. In this way, consequences drive behaviour. This is the foundation of learning. Often we can control the variables, like saying a cue or presenting a reward, but your dog will also find their own cues and consequences. It’s important to be aware of what you are conditioning, but also what their environment may be reinforcing or punishing!

Your dog also decides what is reinforcing to them, so observing what they find rewarding will help you in your training. For example, if you offer a kibble when your dog runs toward you at the park, but they run past you to go dig a hole, that means digging a hole is more rewarding to them in that context. You can use this information to adjust the value of your reward (ex. bringing fancier, stinkier treats to the park) and/or temporarily adjust your expectations for recall at the park. Refusing a reward you’ve offered is not your dog “being an asshole”, it’s valuable information that you can use to ensure training success!

It is very important that you don’t use biological needs in training. Withholding food (for survival), shelter, water, exercise, rest, or mental stimulation will not help train your dog. When they are deprived of their basic needs they cannot learn anything and will likely start more ‘bad’ behaviours to fulfill their needs!

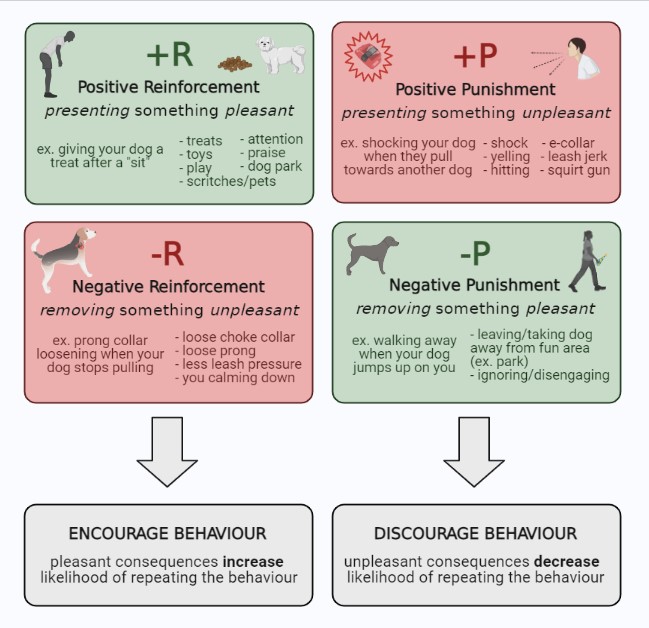

Operant conditioning occurs through any of four quadrants. In this context ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ are not describing how your dog feels about the outcome! Positive means something is being given (think addition for “+”) and negative means something is taken away (think subtraction for “-“). Punishments are consequences that decrease the frequency of a behaviour, and reinforcements increase the frequency.

Trainers use these to encourage desired behaviours (traditional cues: sit, stay, heel, place, go to crate, etc.) and discourage undesired behaviours (jumping up, biting, rough play, inconvenient/destructive chewing, excessive barking, etc.). Reward-based training uses positive reinforcement (+R) and, very occasionally, negative punishment (-P). Aversive training uses positive punishment (+P) and negative reinforcement (-R).

It is important to investigate the training methods used by professional trainers before hiring them! Certified trainers use scientifically-backed +R and -P methods that improve the welfare of dogs and don’t cause harm. Words like “alpha”, “dominance”, “stubborn”, “balanced training”*, and “pack leader” are used by unqualified trainers who use aversive methods. These people are almost never certified, because certifying institutions recognize that a) dominance/alpha theory in dogs has no evidence, and b) aversive training is bad for dogs and never necessary! Do not hire these trainers.

*”Balanced” sounds fine, but that means they use a mix of all four quadrants. Studies have shown that any amount of aversive training, even when combined with reward-based training, decreases welfare and increases long-term stress and behavioural problems. Reward-based training is shown to be more effective, longer-lasting, and better for your dog!

- POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT (reward-based – encourages behaviour)

Positive reinforcement is often the first thing we think of when we think of dog training, and it should be! Rewarding your dog for good behaviour motivates them to do that behaviour more often. This makes your dog want to do the things you want them to do. Positive reinforcement is the most effective way to train behaviours and is very versatile.

One way to mark good behaviour is to wait until your dog performs it on their own, then reward them right away. They remember the behaviours that earn them rewards and will offer them up more often. Once they get the hang of the behaviour you want them to perform, you can add in a cue (verbal, whistle, hand gesture, whatever!) as they are doing it and continue to reward. Your dog will build the association between the cue, the behaviour, and the reward, and offer the behaviour in response to the cue!

You can also use ‘shaping‘ to positively reinforce behaviour. This means you selectively reward your dog for behaviours that are closer and closer to the one you want them to do. You can lure your dog into position using treats, or build the goal behaviour by waiting and marking similar behaviours.

For example, when training “down”, some trainers recommend you have the dog sit and then move a treat under their belly, so they have to scooch back and lie down to get it. Other dogs respond better to starting in a sit and following the treat along the ground away from their body, but this has to be done slowly (or they will just get up and walk to it). Alternatively, you can mark, reward, and say your cue when the dog lies down outside of a training session. You can also mark behaviours progressively closer to a full “down” until your dog gets the point. I tend to use a combination of the above, then practice the behaviour in new environments to make sure they have it rock solid!

- POSITIVE PUNISHMENT (aversive – discourages behaviour)

Positive punishment uses discomfort, pain, and/or fear as consequences for undesired behaviours. Negative consequences following a behaviour make your dog less likely to perform that behaviour again.

Positive punishment makes your dog comply out of fear, pain, and/or annoyance. This can damage your relationship with your dog because they have been classically conditioned to associate your presence with discomfort. Because positive punishment does not train an alternative to the undesired behaviour, your dog has no information on what you do want from them; this sets them up for failure! Punished behaviours are also often natural for dogs, and they need an outlet for these impulses. Dogs need to be dogs! Aversive training has also been proven to increase reactivity, stress behaviours, and behavioural problems.

Shock and e-collars use positive punishment as an immediate painful consequence, and the shock often continues until the behaviour stops. Relief from the positive punishment is negative reinforcement (see below).

- NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT (aversive – encourages behaviour)

This method takes away the unpleasant consequence when the ‘bad’ behaviour ends. Dogs learn that certain behaviours make the pain stop, so they will be more likely to offer those behaviours. Many “no-pull” tools (like slip leads, prong and choke collars, or face halters) and “no-bark” collars use this principle. These products wouldn’t ‘work’ if they didn’t cause pain and discomfort. The theory is that the dog controls their own pain level, and will learn that if they stop pulling, the pain stops; unfortunately this often doesn’t work, as the tissue can lose feeling and dogs can do serious damage to their necks. They also endure a lot of pain for natural urges like sniffing, walking comfortably, or exploring their environment.

Some other tools, like Martingale collars, are used this way by misinformed trainers. Martingale collars are designed to tighten only slightly to prevent small-headed dogs from escaping their collars. When these collars (or regular flat collars) are fitted improperly and/or used for leash jerks or pull-deterring, they can cause harm to dogs including skin irritation, honking cough, and tracheal collapse.

Negative reinforcement is often the end of a positive punishment. Other forms of negative reinforcement include natural consequences, like pulling away from a hot stove or leaving a stressful environment.

- NEGATIVE PUNISHMENT (reward-based – discourages behaviour)

Think “time-out” or losing privileges. Negative punishment takes away something your dog likes as a consequence for ‘bad’ behaviour. This is used sparingly by reward-based trainers; it does not cause harm to the dog because it is only taking away a ‘bonus’ good thing, but improper negative punishment can lead to trust issues and resource guarding. It is important to only use this under specific direction from a qualified trainer, and is best avoided if your dog has issues with resource guarding.

Negative punishment can be used for behaviours that are difficult to positively reinforce. When your dog is greeting you and jumping up to say hello, rewards for ‘calm’ behaviour can get lost in the excitement. In this scenario, pulling away until your dog has four paws on the ground can be effective. By disengaging temporarily, you have withdrawn the reward (interacting with you) while your dog performs the undesired behaviour (jumping up). As soon as they go back to the desired behaviour (standing), you re-engage and the reward comes back, positively reinforcing the standing behaviour.

SO WHAT?

Scientifically-backed training techniques are based on the fundamentals of animal behaviour. These principles can be used to understand, evaluate, and redirect behaviours you wish your dog wouldn’t do, and sets you up to have a mutually loving relationship! Reward-based training allows you to understand your dog and your dog to understand you. Stay tuned for more posts in the Behaviour 101 series, and feel free to reach out for more information!

If you’d like to do further reading on animal behaviour, I recommend reading the following free resources:

Does training method matter? Evidence for the negative impact of aversive-based methods on companion dog welfare (plos.org)

The Welfare Consequences and Efficacy of Training Pet Dogs with Remote Electronic Training Collars in Comparison to Reward Based Training (plos.org)

Animals | Free Full-Text | Behavioural Evaluation of a Leash Tension Meter Which Measures Pull Direction and Force during Human–Dog On-Leash Walks (mdpi.com)

These three are behind a pay wall, but I will be posting lay summaries soon 🙂

The relationship between training methods and the occurrence of behavior problems, as reported by owners, in a population of domestic dogs – ScienceDirect

The effect of frequency and duration of training sessions on acquisition and long-term memory in dogs – ScienceDirect

That Dog Is Smarter Than You Know: Advances in Understanding Canine Learning, Memory, and Cognition – ScienceDirect